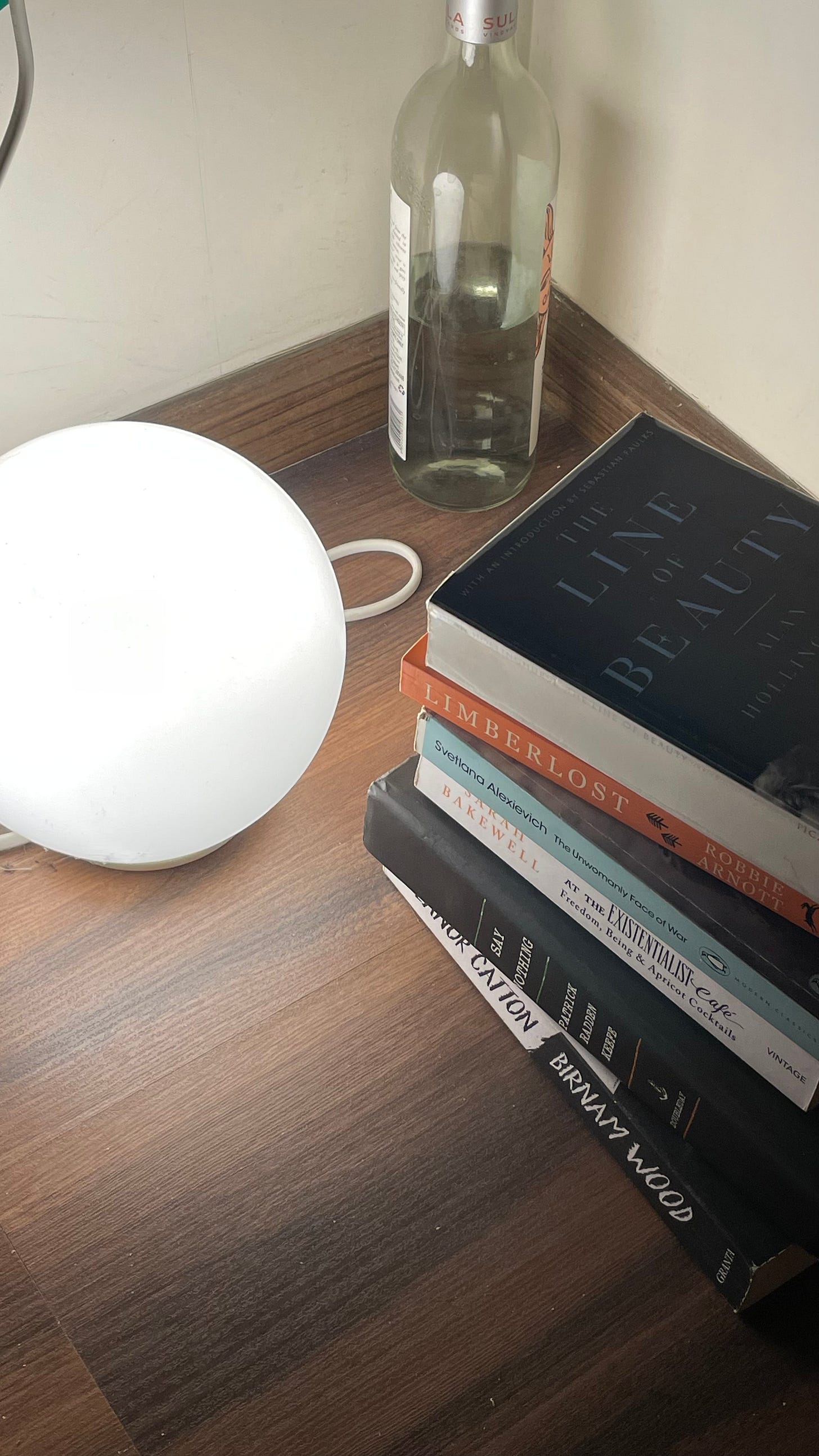

2023 in reading

Not necessarily fresh releases, but a mix of new and old, fiction and nonfiction.

This was an interesting reading year. I didn’t read “a lot”, left unfinished about a dozen books, read some on and off over weeks — and at times, months — and only really, truly, deeply loved a handful. But I did cross paths with books that opened new doors, that thought in new and interesting ways, were fun, or ones that simply came at the right time. What I read and what I look for in reading were a little more elusive this year, and through the year, books felt everything from just right to disparate pieces that didn’t quite fit together in what I think is my taste. Now, however, as I sit back and write this, I see preferences, themes, and what I want literature to do falling into place.

Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez (trans. Megan MacDowell)

They sought me out, here I am. I don't know how to let go of the dead.

On the face of it, this sprawling book about a mysterious cult known as the ‘Order’ is horror of the kind Enriquez has been workshopping in her stories in The Dangers of Smoking in Bed and Things We Lost in the Fire. But stand back a little, and Our Share of Night is a family novel. Juan and his son Gaspar possess the ability to commune with the dead and summon the devil (“the Darkness”) and are at the centre of the Order led by the Bradford-Reyes family between Buenos Aires and Misiones. The plot reveals itself through multiple characters working at different levels of the Order and in different timelines. The gothic lurks at the margins and just under the surface of all that is revealed: the Darkness exists in liminal spaces like abandoned houses, empty rooms, and ghost towns. Finally — and what is my favourite thing about the book — it borrows creatively from the time in Argentina it is set in. Much of the substance of the horror comes from the everyday violence and repression of the military junta. Abandoned houses, military prisons, and mass graves are often sites where the Darkness is at its most powerful. The Order and the military complement each other in how violence and surveillance envelop the characters. Our Share of Night is persistently unsettling and has set itself up to be a novel I will seek to reread from time to time.

The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst

Nick smiled to himself at the flat’s pretensions, but inhabited it with his old wistful keenness, as he did the Feddens’ house, as a fantasy of prosperity that he could share, and as the habitat of a man he was in love with. He felt he took to it well, the comfort and convenience, the discreet glimpsed world of the things that the rich had done for them. It was a system of minimised stress, of guaranteed flattery.

There was a certain Englishness to the prose in The Line of Beauty that I have struggled to accurately describe ever since I first read the book. More than the plot itself, it was Hollinghurst’s writing that hit the nail on the head for me: it is exact while also being lush and intricate. It straddles a five-year period that coincides with Margaret Thatcher’s first term (1983—87). In college, Nick becomes close friends with a Tory family (the Feddens, via the son Toby) and is pulled, in a Nick Carraway-esque fashion, into the world of the rich, even as he tries to continue becoming the person he is. The Line of Beauty implicates its time — Thatcher-era England, class, art, queer politics, the AIDS crisis — but not to comment on them. It isn’t “about” any of these things: it is resolutely about Nick and, as and through him, about the Feddens and everything that a glimpse of the “world of the things that the rich had done” brings to him.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton

“There’s something so joyless about the left these days,’ Tony continued, ‘so forbidding and self-denying. And policing. No one’s having any fun, we’re all just sitting around scolding each other for doing too much or not enough – and it’s like, what kind of vision for the future is that? Where’s the hope? Where’s the humanity? We’re all aspiring to be monks when we could be aspiring to be lovers.”

Also with the kind of closed, plot-led structure I loved in The Line of Beauty is Eleanor Catton’s third book, Birnam Wood. The eponymous activist farming collective, is at the centre of the plot. Early on, its founder and one of the protagonists, Mira, pushes the collective into a deal with Robert Lemoine, a billionaire who offers to invest in the collective’s farming project. Covertly, Lemoine is mining the valley for critical minerals and supposedly building a bunker to live out the end of the planet in. Birnam Wood, like The Line of Beauty, isn’t particularly interested in making a commentary on late-stage capitalism, environmental destruction, or left-wing activism — or, for that matter, in explaining them. Refreshingly, the book is largely agnostic to any social structures (although it deals with them in highly intelligent and fun ways): characters discuss them and fight over their legitimacy, but Catton makes sure they do so within the confines of what her plot will let them do. Equally fascinating is how the plot reveals itself through a great deal of misdirection. Frequently, the book hints itself heading in one direction, only to veer off sharply and skillfully in a whole new one. Nothing about the book and its end was predictable, yet somehow, it was the only end possible — and satisfying to a T.

Limberlost by Robbie Arnott

He'd stare at that field of water until all the things he could not handle were rinsed out of him, and all that remained within him was the memory of that night: the whale, the warmth of the coat, his brothers, his father, the starlight. Afterwards, he'd turn around and sail for home, which would take the rest of the day, probably some of the evening. With luck, he'd make it back to Limberlost before it was completely dark.

Among the quieter books I read this year was this bildungsroman set in a landscape Arnott writes of with so much love and kindness. The book follows Ned, a Tasmanian farmer, and through his eyes, his changing orchard and a stable but changing relationship with nature. As a child, Ned’s father takes him and his brothers out to the harbour to see a whale rumoured to be terrorising fishing boats in the open sea. This event and how Ned remembers it is Limberlost’s pivot. In all his actions on the farm, in all his decisions about family and business, and his ruminations while driving through the island, Ned keeps returning to the whale and — more importantly — his childhood dreams of sailing away. In bits and pieces, if you pay attention, Limberlost is also about small but incremental changes in Ned’s landscape. Early on in the novel, he goes on a trip to study new methods of pesticide farming and meets with the company executives. His daughters, in time, raise questions about being settlers on indigenous land, leading Ned into a beautifully executed internal monologue about land, nature, farming, and growth. Limberlost’s finest pages are its final ones when Arnott reveals his most closely guarded plot points and lets the reader sit with the moral fallout from them.

Say Nothing by Patrick Radden-Keefe

Think of the armed struggle as the launch of a boat, Hughes said, getting a hundred people to push this boat out. This boat is stuck in the sand, right, and then get them to push the boat out and then the boat sailing off and leaving the hundred people behind, right. That’s the way I feel. The boat is away, sailing on the high seas, with all the luxuries that it brings, and the poor people that launched the boat are left sitting in the muck and the dirt and the shit and the sand, behind.

Say Nothing is both a history and an epilogue. It tells the story of the Troubles in Northern Ireland like fiction would: through the entangled lives of four people — Jean McConville, a widow among the several people ‘disappeared’ during the Troubles, and members of the Provisional IRA, Brendan Hughes, Gerry Adams, and the Price sisters. The book’s thrust is the Irish Republican Army: its organisation, activities, and its relationship with the Irish society in theory and practice. The Troubles play out between the trajectories of its ‘protagonists’’ actions and motivations, with the McConvilles serving as the strongest reminder of the IRA’s morally dubious involvement in disappearing people. In its final pages, Say Nothing neatly unpacks the unfinished business that the Troubles were, and the stalemate they ended with. What happens after a war that was never formally a war? What comes after a revolution that never became a revolution? What do soldiers do when a war that was never called a war, ends? Who gets to tell the story? The book follows the questions it opens with to the very end. And it is this epilogue that is the story many former colonies — including my own — where freedom was fought for violently and politically and for a long period, but which ultimately came with a confounding sense of stalemate. Northern Ireland’s tense relationship with the Troubles, partly because of how recent they were, partly because how total colonialism and anti-colonialism is, is alive in a way that is familiar. Then there is the language: “Troubles” minimises the decades’ violence in much the same way that “Mutiny” denies Indian uprisings of their politics. I’m not sure still, if the book is more effective because it deals with questions that have become my business, but it is certainly more loved because it is close to everything that occupies so much of my headspace.

The Overcrowded Barracoon by V. S. Naipaul

Incapable of lasting reform, or of a correct interpretation of the new world, India is, profoundly dependent. She depends on others now both for questions and answers; foreign journalists are more important in India than in any other country. And India is fragmented; it is part of her independence. This is not the fragmentation of region, religion or caste. It is the fragmentation of a country held together by no intellectual current, no developing inner life of its own. It is the fragmentation of a country without even an idea of a graded but linked society.

Naipaul first visited India in the 1960s, a journey that “broke his life into two” — the same decade as when he extensively travelled the postcolonial ‘Third World’. The Overcrowded Barracoon is collected articles from those years. A clinical and moving bunch on the impossibility of decolonisation and the long shadow of empires; on his encounter with India in a decade of famine, war, drought, and reform; a fragmented country "without even an idea of a graded but linked society"; on the teeming mass of former ‘colonials’ who can’t help but seek out a metropolitan life. Contemporary writing is especially special to me, and I loved this to bits, also because everything Naipaul contends with in his essays has come to me, over the years, through academic papers and books on the knowledge project that colonisation and decolonisation are. Discovering The Overcrowded Barracoon was like being handed a glimpse into postcolonial thought before it was called postcolonial thought.

At the Existentialist Café by Sarah Bakewell

It is perfectly true, as philosophers say, that life must be understood backwards. But they forget the other proposition, that it must be lived forwards. And if one thinks over that proposition it becomes more and more evident that life can never really be understood in time because at no particular moment can I find the necessary resting-place from which to understand it.

This history of modern existentialism, as Sartre, Beauvoir, Merleau-Ponty, Camus, Heidegger and others explored it in 20th century Europe, is written with so much love and enthusiasm for the subject. Bakewell’s chosen philosophers met and interacted in (in cafés, typically) the heady time that interwar and postwar Europe was, and the book is adept at drawing the line between the era’s tensions and their reflection in the philosophy of the time. At the Existentialist Café deals with the complicated histories of Heidegger and Camus, and therein the rifts within existentialism as theory and as practice head-on. It is a story told extremely finely: philosophy is all at once a conservation, a collective human project, and a deeply personal response to the world that has been emerging since the 1920s.

The Unwomanly Face of War by Svetlana Alexievich

Whatever women talk about, the thought is constantly present in them: war is first of all murder, and then hard work. And then simply ordinary life: singing, falling in love, putting your hair in curlers …

This a collection of eye-witness accounts of the Second World War, as seen by women who fought in the Soviet Army, is quite literally cavernous. It was the scale of conflict in World War II that led to large-scale deployment of women across Allied and Axis armies: 225,000 in the British Army, about 500,000 in the German forces, and around a million among the Soviets. Alexievich brings these women together who, during the war fought alongside men in the Red Army and among partisan (militias formed to fight the occupying Nazi Army) groups, but who, after the war, were rapidly forgotten and went back to “their world”. The book is, from the get-go, an exercise in documenting the varied roles women played — from being active combatants to snipers and mechanics, and further on to what she calls the “second front”: nurses, cooks, doctors, radio operators, and clerks. The accounts dance around womanhood, and Alexievich works to excavate gender and femininity in the time of war. But that is not all Unwomanly Face does; it is a book as much about the war as it is about women – perhaps even marginally more about the war. The arrangement of oral histories and memories in the book is meant to add to our picture of war in all its brutality. “I write not about war, but about human beings in war,” writes Alexievich, and to that end, writing about women’s war is a means of accessing a history of war that political and military histories ignore: “their war has smell, has colour, a detailed world of existence.” The Unwomanly Face of War is all at once about the women, the World War, and the Soviet Army, as also an exploration of why women’s wars are invariably not the stuff of war history.

How was your year in reading? If you’ve read any of these and/or have favourites from the year, I’d love to hear it!

Warmly,

C.

I loved reading this! I had Limberlost on my tbr because of one of your Instagram posts, but your summary here makes me wanna read it even more; it sounds just like my cup of tea 😄

I always loved reading your blog. I kept waiting for it. Added The Unwomanly Face of War.